Zero-width characters explained

Zero-width characters are invisible Unicode marks that occupy a real position in a text stream while rendering no visible glyph. They can sit inside a word, between letters, inside a hashtag, or next to an emoji, and still remain undetectable by eye. Their impact is structural rather than visual: they can change how text is segmented, parsed, matched, or interpreted by platforms and applications. That is why zero-width artifacts often appear as “random” formatting bugs even when the text looks perfectly normal.

In modern publishing workflows, zero-width characters become a practical problem because they are frequently transported through copy-paste, rich text conversions, and chat interfaces. Some of them are legitimate and necessary in specific writing systems. Others appear unintentionally as a side effect of formatting layers. The challenge is not only detection, but safe normalization: removing unwanted zero-width marks while preserving meaning, emoji behavior, and multilingual text integrity.

Zero-width characters are part of the broader invisible Unicode landscape. The Invisible Unicode characters guide provides the overall map. For space-related layout failures, the companion reference is Non-breaking spaces (NBSP) in text, because NBSP and zero-width artifacts often surface together in the same copy-paste pipeline.

What they are

Zero-width characters are Unicode code points that take space in the character sequence but do not render as visible marks in typical interfaces. Unlike a normal space, they do not create visible separation. Unlike NBSP, they do not primarily control wrapping. Their main effect is segmentation: they can introduce invisible boundaries, join visible symbols, or prevent joins depending on the specific code point.

The most commonly encountered types in everyday workflows are zero-width space (ZWSP, U+200B), zero-width joiner (ZWJ, U+200D), and zero-width non-joiner (ZWNJ, U+200C). They often appear near emojis, punctuation, or copied fragments. Their presence is not always malicious or intentional. However, in platform-sensitive contexts, they can change how tokens are detected, how hashtags match, and how editors behave.

ZWSP (U+200B): invisible boundary

Zero-width space is often used to allow line breaks in scripts or to insert a soft boundary without visible spacing. In modern workflows, it can appear unintentionally and act as a hidden separator inside hashtags or words. A hashtag can look intact to humans, yet be split structurally into two parts for the platform, causing it to stop being recognized.

ZWJ (U+200D): invisible glue

Zero-width joiner is used to join characters for correct shaping in some writing systems and to build emoji sequences. It is a legitimate part of many emojis. The key nuance is that removing ZWJ blindly can break emoji rendering or change how combined emojis display. Safe cleanup must distinguish between unwanted ZWJ in text and required ZWJ in emoji sequences.

ZWNJ (U+200C): invisible separator

Zero-width non-joiner prevents joining behavior in scripts where joining would otherwise occur. In typical Latin workflows, ZWNJ can still appear through copy-paste or conversions and behave like a hidden token boundary. Its impact is usually felt through selection quirks, parsing anomalies, or inconsistent matching.

Why they appear in modern workflows

Zero-width artifacts typically enter text through workflows that preserve rich formatting or that render content through multiple layers before it is copied. Chat interfaces, document editors, and web pages can carry invisible separators into the clipboard package. Then, destination apps interpret the text according to their own tokenization and parsing rules. What looks identical can behave differently because invisible code points create invisible structure.

In 2025 workflows, AI-generated text is frequently transported through chat interfaces optimized for readability. The risk is not intent, but layering. The same text can pass through markdown rendering, typography rules, and clipboard conversion. That pipeline increases the chance that invisible separators survive and later interfere with platform parsing.

Why social platforms are sensitive

Social platforms are not neutral editors. They parse text for features such as hashtags, mentions, links, previews, and truncation. Invisible boundaries can alter token detection. That is why zero-width artifacts often surface as broken hashtags, non-clickable mentions, or inconsistent snippet behavior. Platform-specific references like clean AI text for Instagram and clean AI text for LinkedIn remain relevant when publishing workflows involve copy-paste from rich sources.

Common symptoms

Zero-width issues rarely look like corrupted text. They look like normal text that fails to behave normally. The most common symptoms are broken hashtags, inconsistent matching, unexpected cursor movement, and selection boundaries that feel “off”. In some cases, text may wrap or truncate in ways that are hard to predict because invisible boundaries change tokenization and line-break decisions.

A typical pattern is a hashtag that looks correct but does not register as a hashtag. Another pattern is a word that cannot be selected as a whole, or that splits unexpectedly during editing. These symptoms are disproportionately common when content is copied from chat interfaces, PDFs, Docs, or web pages.

How to detect them

Zero-width characters are difficult to detect because they have no visible glyph. Find/Replace cannot reliably target “nothing”, and many editors do not expose code points. Reliable detection comes from either revealing invisibles in a code-aware environment or using a tool that can normalize text safely without requiring manual inspection.

Method 1: reveal invisibles in a code-aware editor

Some editors can display zero-width marks as symbols. This is useful for diagnosis, but it is not scalable for high-volume publishing workflows, especially when content is created and posted directly from mobile.

Method 2: inspect Unicode code points

Code point inspection confirms whether ZWSP, ZWJ, or ZWNJ is present. This is the highest-confidence method, but it adds friction to workflows. It is best used to validate a suspicion or to debug recurring issues in a content pipeline.

Method 3: symptom-driven validation

When a hashtag refuses to register, when a word splits oddly, or when selection boundaries behave unexpectedly, zero-width artifacts are likely. This method is not proof, but it is a pragmatic signal that becomes strong when combined with known high-risk sources.

How to fix them safely

Safe cleanup requires controlled normalization. Zero-width characters are not uniformly unwanted. ZWJ is required for many emoji sequences and for some scripts. ZWNJ is legitimate in certain languages. Blind removal can break meaning or rendering. The best approach is to remove zero-width artifacts that are unintended in common publishing contexts while preserving those that are structurally required.

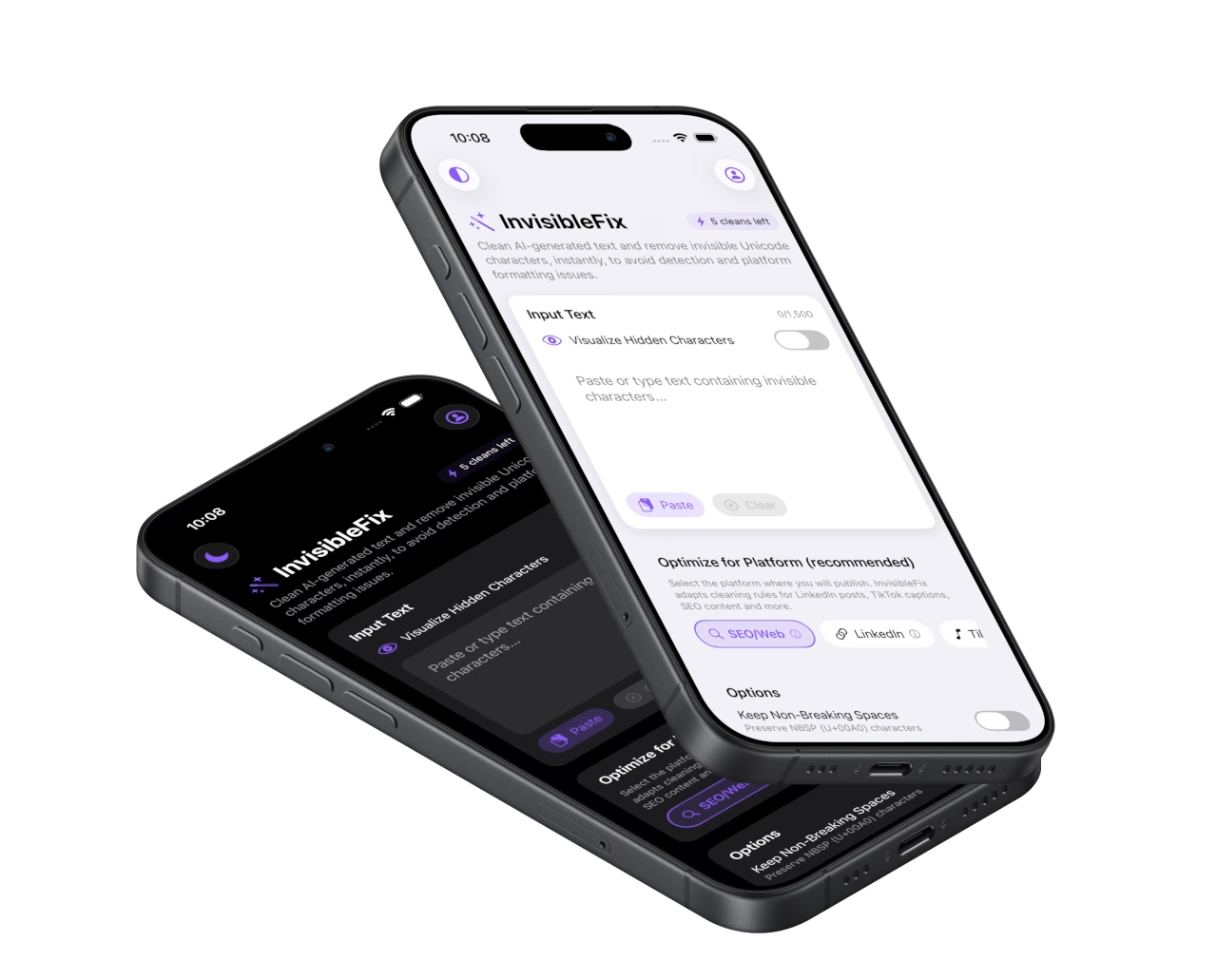

In practice, most marketing and publishing workflows benefit from normalization before posting to social platforms, CMS fields, and mobile-first surfaces, where predictable tokenization and stable parsing matter more than typographic nuance. The Unicode hygiene checklist summarizes a repeatable process. For immediate cleanup, text can be normalized locally in the web app at app.invisiblefix.app.

Once zero-width artifacts are normalized, hashtags and mentions become reliably parsable again, selection becomes predictable, and text stops behaving “haunted” across platforms.